Works, including

Master Harold ... and the Boys

(1982), of South African playwright and director Athol Fugard explore racial tension and inequality especially during apartheid.

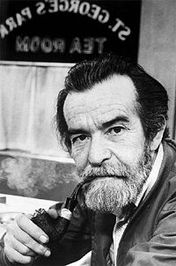

Harold Athol Lannigan Fugard, better known as Athol Fugard, acted. Sheila Fugard, his wife, and Lisa Fugard, their daughter, also follow.

An Afrikaner mother bore Athol Fugard to a Roman Catholic father of Irish extraction. He considers an Afrikaner but in English reaches a larger audience. After his birth, his family quickly moved to Port Elizabeth. In 1938, the Marist brothers college, a Roman Catholic primary school, enrolled him. Awarded a scholarship, he afterward enrolled at the local technical college for his secondary education. He then enrolled in the University of Cape Town but dropped. He sailed around the world, mainly in the Far East, on ships.

Fugard married Sheila Meiring, now known as Sheila Fugard, then an actress, in September 1956. She later authored novels and poems in her own right. They started the serpent in Port Elizabeth before moving to Johannesburg, where a court employed him as a clerk.

Fugard saw suffering under the pass laws, and the court environment provided a firsthand insight into the injustice and pain.

With Zakes Mokae and a group of black actors, Fugard first started with

No Good Friday

. Returning to Port Elizabeth in the early 1960s, he with a group of actors first performed in the former snake pit of the zoo, hence the name, the serpent.

The political slant bought him into conflict with the government. To avoid prosecution, he started to take overseas. After people produced

Blood Knot

in England, they withdrew his passport for four years. In 1962, his public support for an international boycott against segregated theater audiences led to further restrictions.

He extensively with John Kani and Winston Ntshona, black actors, shopped

Sizwe Banzi is Dead

,

The Island

, and

Statements after an Arrest under the Immorality Act

.

He early shopped with Kani and Ntshona and staged dramas in black areas for a night, and the cast then moved to the next venue, probably a dimly lit church hall or community center. The audience, normally poor migrants, labored and resided hostels in the townships. At this time, politics mirrored the frustrations in the lives of the audience. Fugard drew the audience into the drama; members applauded, cried, and interjected their own opinions. From the audience, Fugard used feedback to improve; he expanded and deleted the parts.

For example in

Sizwe Banzi is Dead

, migrant Bansi assumes identity and gets the important pass to get a job only to survive. When he debates worthiness of sacrifice of the effective "death" of Sizwe, the audience appreciated a nonentity without a pass and consequently cried out, “Go on, do it!"

People improvised available sets and props, which helps to explain the use of the minimalist productions. In 1971, people eased the restrictions against Fugard and allowed him to travel to England to

Boesman and Lena

. In 1982, he composed a semi-autobiographical drama.

Fugard showed against injustice on both sides of the fence and in

My Children! My Africa!

attacked the national congress for deciding to boycott schools to cause the damage that he recognized to a generation of pupils.

With the demise, Fugard first performed

Valley Song

and

The Captain's Tiger

focused on personal rather than political issues.

People regularly produce, and he won many awards.